Modern cameras have embraced the concept of high dynamic range, high resolution, and perfect color reproduction. So much so that it feels like looking through a window when we watch movies.

But when using these tools to try and capture the nostalgia of the 80s and 90s, creatives always have a hard time finding the grunge of those eras when their initial composition is too clean.

Cinematographer Alexander Chinnici and the team behind the V/H/S/85 “wrap around” “TOTAL COPY,” decided the best way to dirty up the frame, was to go back in time.

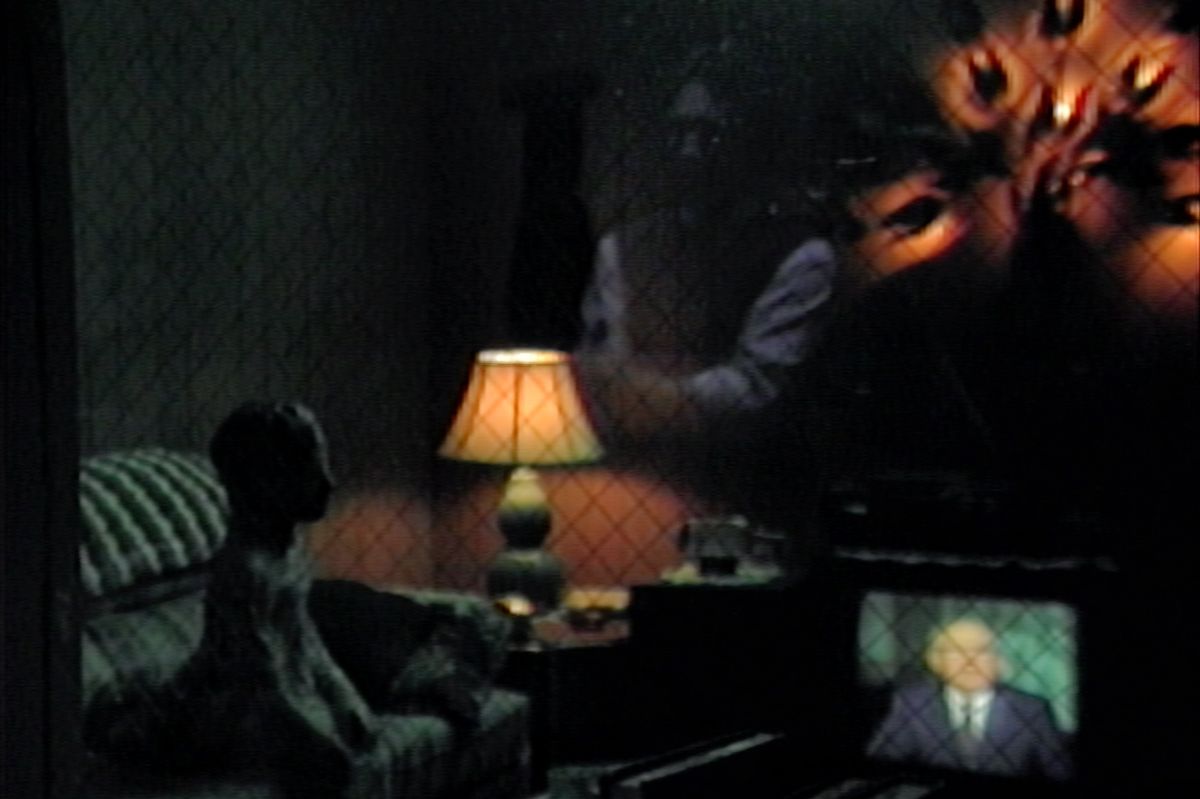

Directed by David Bruckner, “TOTAL COPY” used the unique approach of shooting on 40-year-old analog cameras and quite literally flicking the magnetic tape of a VHS cassette to get the effects they wanted.

We spoke with Chinnici about his workflow and experience on set to learn more.

No Film School: Can you tell us about your initial reaction when you found out you’d be working with David Bruckner on this project, especially given his notable works like Ritual, Night House, Hellraiser, and the original V/H/S?

Alexander Chinnici: Fortunately, Dave and I have been friends for a couple of years now so we already knew one another. Like many, I am a fan of his work and greatly respect his approach to the craft. We had already spent many nights talking shop and realizing how closely aligned we were. He started off by explaining to me that we are the bottom layer of the tapes, the mud. That was the approach for the wrap around on this one. It was exciting to embrace the exact opposite of what I have been doing for years. My job is often to make things look “pretty” (for lack of a better word) here it was to make it rough and authentic but also fun to look at. Striking that balance was a unique challenge.

For me, found footage is all about tricking the audience. That tiny doubt in the back of their head. Is this real? I’ll never forget seeing The Blair Witch Project for the first time. Getting the right look for “TOTAL COPY” initially resulted in doing a ton of research and from that, creating a bible. We found a lot of inspiring gems on YouTube.

NFS: The use of video tube cameras from the early 1980s is certainly a unique choice. How did you come to the decision to use this vintage technology, and what challenges did you face in sourcing and using them?

Chinnici: I have been fortunate to become friendly with a wonderful filmmaker by the name of Charles Papert. Charles now directs but in his day he was a notable operator and more recently, a successful cinematographer. He operated on so many shows that we know and love, such as West Wing and Scrubs, and movies like American History X. When he moved to shooting, he shot arguably the best comedy sketch show of all time, Key & Peele. If you recall, whenever that show did throwbacks, it was always really authentic. That’s all Charles.

While hanging out over the years, he would occasionally tell me about these old cameras that he had. I personally came up with CCD cameras shot on DV and MiniDV, I knew very little about video cameras that pre-dated that technology. One of my first thoughts was, “What about Charles’ cameras?” I pitched it to Bruckner, and we set up a test. Right away, Dave identified the need for two approaches. The TV crew that shot for “TOTAL COPY” and the local videographer hired by the university, which would eventually lead to the more traditional found footage ending.

The people who worked on “TOTAL COPY” would use the broadcast camera that Charles had (JVC KY1900), the higher end of what was available. It has a total of three tubes, the resolution was 480, and the lens was an actual broadcast lens. We used this for the shots of Drake, the host, the interviews of Sarah Grayson after the events, the exteriors of the campus, and the cutaways of the soap opera that Rory mimics early on.

For the University’s/Dr. Spratling’s “home movies”, we used the more lo-fi, Magnavox Mini camera. This camera has a fixed lens, 240 resolution, and is a single tube camera.

Besides the Frankenstein build that we had to configure being difficult, the iris on this camera was a little dial with zero marks that would freely spin. I quickly discovered a lot of idiosyncrasies with a camera like this.

I found a few tricks to make the camera “happy” but also found other ways to really push the aesthetic of it. It was a learning-as-you-go experience despite having done a lot of tests with it.

Charles has the cameras configured in such a way that they go out to a decimator and into an Atomos recorder. This way, you can record 1080 ProRes422, progressive, etc.–you have a series of options to choose from. Assistants Amanda Morgan, Ian Barbella, and Steve Wyshywaniuk helped set me up for success. It did take a lot of tinkering, but the results are well worth it. It was also configured to have a wireless video out and the ability to take on modern batteries.

Besides concerns of reliability, the old tube cameras can also have the highlights literally burned right into the tubes. Charles cautioned us, rightfully so. It was nerve-wracking and something that we had to be really aware of. I likely annoyed everyone by how often I had to turn away or put my hand in front of the lens, especially when they were trying to see something. I am personally very offended by clipped video highlights. They drive me nuts. However, I somehow turned that into something that I loved here. It really lends to the right look that these cameras had. Balancing that with not killing the camera was a real challenge.

In the end, it is incredible that 40-year-old video cameras hold up during very rigorous productions. Our smartphones start to bail on us after two years. So it is a testament to the older analog technology.

Charles was also very helpful in keeping me honest with the lighting and the filtration that I used for the interview, host coverage, and the soap opera. I think he enjoyed reminiscing and sharing the techniques. It was exciting to learn about a time that I knew little about—the right light units, angles, ratios, what type of diffusion, and lens filtration. Studying the reference videos and brainstorming with Charles was instrumental to the look.

Gaffer Edgar Gomez and Key Grip John Morgan took the ball and ran away with it on set. We often had to light the sets or the locations more so than set ups, directions, or shots. Found footage often requires at least a 270 resolution world. Also, learning “how” to light for such cameras took a second, but we figured it out!

NFS: Transferring the footage to VHS tape must have added an extra layer of nostalgia to the project. What was the motivation behind this decision, and how do you believe it influenced the final aesthetic of the film?

Chinnici: It had a huge effect on the final film. We knew that while the camera choice that we had made was right on the money, it still needed to feel like you were actually watching a VHS tape. There are so many little aesthetic things that lend to this experience. The more research that we did, the more testing, it became clear that we had to do this authentically.

My wife Natasha Kermani directed the short “TKNGD” (techno-god), which is also a part of V/H/S/85, shot by good friend and wonderful DP Julia Swain. Their piece has a fully VFX world at some point. Natasha and her team at Illium Pictures involved our good friend from college, Forrest McClain, a lover of all things analog (he fixes old video game consoles for fun!). They had Forrest start with these basic VHS transfers to help degrade the CG character in an analog way. Around this time, Dave and I were heating up our prep for “TOTAL COPY.” It was neat because both films were helping one another through the kinds of asks and testing we were doing for our respective pieces. Eventually, Mike Nelson’s “NO WAKE” would go on to use this process as well.

Like Charles, Forrest was really patient with us. We tested this process a lot. We found ways to increase the fidelity from a basic pass, to avoiding drop frames, or aspect ratio issues, you name it (shout out to Sean Lewis at Soap Box Films and editor Thom Newell for also being incredibly patient and helping us figure all of it out). Also, the technique would alter the look of the piece greatly. We found we had to “pre-color” the footage to offset the changes. The blacks would get super crushed, and we’d lose a lot of color detail. In the end, no matter what, we did lose a fair amount (and, of course, it got a lot softer), but it was totally worth the trade-off and only added to the many layers of aesthetic fun.

We did a lot of passes with the VCR, we took those files, and Sean at SoapBox conformed it all so that they were in sync and layered on top of one another. Dave and I stayed up one-night picking and choosing the different “takes” of glitches. In addition, we found that we could combine takes and adjust the levels of opacity. Say we wanted it really funky? Take a version that was all fucked up. Maybe sharper? OK. Take the camera original at 70% and just 30% of a cleaner VHS pass. In the end we always made sure that the edge of the frame had some fuzz for consistency. But we also had to make sure that we didn’t step on moments too much.

At the very end, we did the final color pass. This was simply to match a few things, especially in the final shot, the seven minute oner, helping to smooth some moments out. The footage couldn’t hold up to too much more anyway ha.

I should also mention that we did a full test where we filmed the piece off of a CRT television with a high end camera. It looked really special but just screamed that you were watching it off of a screen as opposed to experiencing a tape. The point is, we just about tested everything under the sun to get the right look. We could still be testing now if the release date hadn’t come up!

NFS: The concept of manually introducing glitches directly to the tape by opening up the VCR is fascinating. Can you delve deeper into the process and explain how you achieved this effect?

Chinnici: One of the first things that Dave sent me were some links about Glitch Art which I highly recommend looking into. It is the use of analog video and “breaking” it to make something unique. Most found footage movies use these digital post “glitches” to hide cuts and combine takes. We swore that we wouldn’t depend on that and I am very happy to say that we pulled this off. I found a guy on eBay that was selling this little glitch device. It looked like a pedal that a guitarist would use. It had RCA in and out cables and we patched it into Forrest’s VCR setup.

Dave played it like an instrument to certain beats. In the end, it proved to be too “loud,” and it overstepped aesthetically. However, it did make its way into some transitions (most notably the first 30 seconds of the movie where a certain someone makes an appearance) and the very, very end of the movie.

At some point, Dave had come across a YouTube video of a guy fixing his VCR. In it, he had the top cover off and was screwing in certain parts. As he did so, the image on his CRT was adjusting. It was funny because a video about trying to eliminate these “mistakes” was the inspiration for us to do the exact opposite.

Dave bought some junk VCRs, and over several occasions (and one dead VCR, R.I.P.) we played with screwdrivers, shaking the chassis and just using our fingers to interact with the moving parts. Most notably, literally just flicking the tape while it ran through the machine. We quickly found out that using magnets was a bad idea.

So, I am proud to say that all of the glitches and fun little analog effects that you see in “TOTAL COPY” and through the other various transitions between each short in V/H/S/85 are 110% analog. Another goal that we set for ourselves.

NFS: Do you believe that employing these analog techniques and tangible distortions offers something different than what could be achieved with modern-day digital effects? If so, what?

Chinnici: I do think that it is different. The truth is, maybe a lot of people wouldn’t notice or care. What matters most is that we stayed true to our goal. At the end of the day, you cannot control how people will react. What you can control is how much effort you put in. I care a lot about the process, it is important to not give up until they rip it away from you. Dave is the same. To my eye and a few others, you can definitely see a difference between what we did and what digital effects can do. If I showed you a side-by-side, it would be very clear. But I am aware that I am someone who searches for these kinds of things. What I can tell you is that many, especially older folks, have a smile on their face that looks undeniable to me.

Specifically? The scan lines. Those stand out to me as something very special that, if overlayed, wouldn’t have looked the same. The tape also added a texture that is hard to describe and that I have yet to see a digital effect emulate accurately. It swirls in a way that is very odd. I also think a big mistake that a lot of people make in these formats is sensor size, focal length, T-stop, and, ultimately, the depth of field. It was very obvious to me that much more shallow DOF images are shot on a more modern format. I also don’t see why you wouldn’t want to go down this rabbit hole!

When the hell else would we get the chance to do something like this? Not only to research, learn, and obsess over all things analog but also to take someone else’s money and make something so gnarly? Something so low in resolution? Especially in a time when mandates require 4K this, HDR that… Dave and I couldn’t have passed up this rare opportunity. Also, this year, the strike has been really tough on people. Work is slow, people are scared, and the whole AI thing (which inspired the story of Rory), so to be able to sink our teeth into this? It was a great way to distract ourselves.

NFS: V/H/S/85 will be available on Shudder and also showcased at film festivals. How do you anticipate the audience’s reception, given the unconventional techniques used? Are there any particular reactions or feedback you’re eagerly awaiting?

Chinnici: It premiered at Fantastic Fest in Austin and played again at Beyond Fest here in LA. It was released on SHUDDER/AMC+ on October 6, so it is out!

Fortunately, a lot of folks are really appreciating the authentic approach that we took. Shooting on a VHS camera, shooting on Super 8 film, or doing the same VHS transfer process with Forrest.

I think that we have lived in a Stranger Things version of the ‘80s aesthetic for a while now. Due to this being found footage and especially since ours is literally mimicking (wink, wink) an old TV doc series à la PBS FrontLine, Unsolved Mysteries, etc. it was important that we were much more authentic.

A few audience members who actually lived through the time had big smirks on their faces. A sort of “I remember when my parents would watch…” a genuine nostalgia that brought them back. That feels good. This biggest compliment was tricking them into being unsure of what was stock and what we shot. It’s fun to see where people have gotten it wrong.

NFS: Can you share some behind-the-scenes moments or challenges that stood out during the production of V/H/S/85?

Chinnici: I was personally very stressed throughout because I wasn’t sure if the cameras would last throughout the shoot. We did in fact have one die on us but we had a lot of backups (thank you, Charles!). We also had some aesthetic surprises.

Firstly, just getting used to the lack of dynamic range, how “soft” it looked (especially compared to what we are used to these days), and the low range of color values. By the time the image passed through the decimator, out of the wireless video and onto the monitor, it honestly looked like shit. It wasn’t until you looked at it on your computer afterward that you really got a sense of what you were looking at. So it was a tiny bit like shooting on film with an SD tap. While stressful, the surprises were really exciting.

We would also get excessive scan lines depending on a few factors. Sometimes, it was due to the image being severely underexposed. Other times, it was just because we were moving around so much. It was almost as if the tubes inside were suffering and it was coming through. For the hand-held moments, I could see it in the image and eventually began to almost “feel it.” Certain movements would increase or decrease it. Fortunately, Dave embraced this. I was just praying that it wouldn’t shut down mid-take!

It is always very important to me that the tools that I bring on are reliable and dependable. That no one is waiting on my team or me. In this instance, it was clear to everyone that we were all willing to take that risk. When it is a choice that is understood by all and truly championed by the leader of the group, a big swing like this can be achieved.

Another element that was unexpected was the camera operator “acting” that found footage can require. It is a really unique experience thinking like the local videographer hired to shoot at this university and how that would inform the camera positions. It was mostly apparent in the final one.

Hitting all of those marks while also trying not to look like a professional camera person. Meanwhile practical effects are being used (they are incredibly difficult and tedious but of course worth it!) and remembering lines of dialogue which was terrifying. I quickly realized that I was Jordan Belfi’s (Dr. Spratling) scene partner in the final scene. It was important that I be in it with him. I had never been in that position before. When you operate, you feel that dance with an actor, this was an entirely new level. Later when I recorded some ADR (Dave and I screaming “DOCTOR!” back and forth at one another is another core memory) this experience was taken further.

I am also happy to say that the feet in frame at the end, the long drag down the hallway, that’s me.

So I got to work with stunt coordinator Kamy Bruder and his team. Feet acting, operating from that angle (and making sure that the camera could slide safely), and now knowing what it feels like to be covered in a lot of blood are another list of things that I can add to the unique experiences of this project!

I should also mention the other department heads that really lent to the authentic look. Production Designer Jessee Clarkson, Costume Designer Abbie Martin, and Casting Director Jeff Gafner. Jessee, being older, would often call out anything that was off or untrue. He kept us very honest when it came to some major choices in prep.

Dave is a great leader because he pushed forward and never looked back. I simply followed. I said to him at the end, I feel like a more complete filmmaker now. I will cherish this experience it, and it will be fascinating to see how it informs more traditional projects moving forward.

NFS: Finally, why is it important to you to discuss this project in such detail? What hopes do you have for this project moving forward?

Chinnici: I just hope that people are inspired. Simply because we often strive for the latest, ground breaking technology when so many great tools are already available to us. I hope that people prioritize a bold look over specs. I think that a lot of folks want the new thing simply because it is new. I’m not saying go shoot on SD and make it look like shit on purpose. I am also not saying to be irresponsible with the tools that you use. As a DP you have to set the production and crew up to succeed. What I am saying is that this is a privilege, to get to play make believe. Be responsible but also, be bold, have fun, take big swings. Audiences deserve it.

Author: NFS Staff

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.