This post was written by Kylee Pena and originally appeared on the Adobe Blog on December 4th, 2023.

As the first feature film entirely shot from one fixed camera angle, Ira relied on Adobe Creative Cloud including Premiere Pro and After Effects, to meticulously craft the film.

Premiere Pro’s integration with After Effects proved invaluable to the project, and no other solutions would have made the process as seamless, especially for a small post-production team. In a conversation with Rosensweig, we explored the intricacies of creating the film and learned about the tools used during post-production, such as Transcriptions.

“SHARE?” made its debut in November. Read on below to get a behind-the-scenes look into this narrative. Watch “SHARE?” now on Video on Demand.

How and where did you first learn to edit?

I attended Penn State University as an undergrad. I was initially a Microbiology major, but thought it would be fun to take an Introduction to Film Production course as a sophomore. This was back in 1996/97, so I initially learned to edit on a VHS to VHS machine. We also learned how to splice actual film together on a Moviola. I quickly fell in love with production and editing and ultimately switched into the Film & Video program.

How do you begin a project/set up your workspace?

I like to start each scene by using the last take of every shot to quickly and roughly edit the scene. Once I have a sense of the sections of each shot that I will likely be using in the edit, I build a sequence that contains all takes of each of those sections, back-to-back, so I can select the best portions of each take to use in the edit. After trying many different processes over the years, I find this method to be the most efficient way to edit a scene.

Tell us about a favorite scene or moment from this project and why it stands out to you.

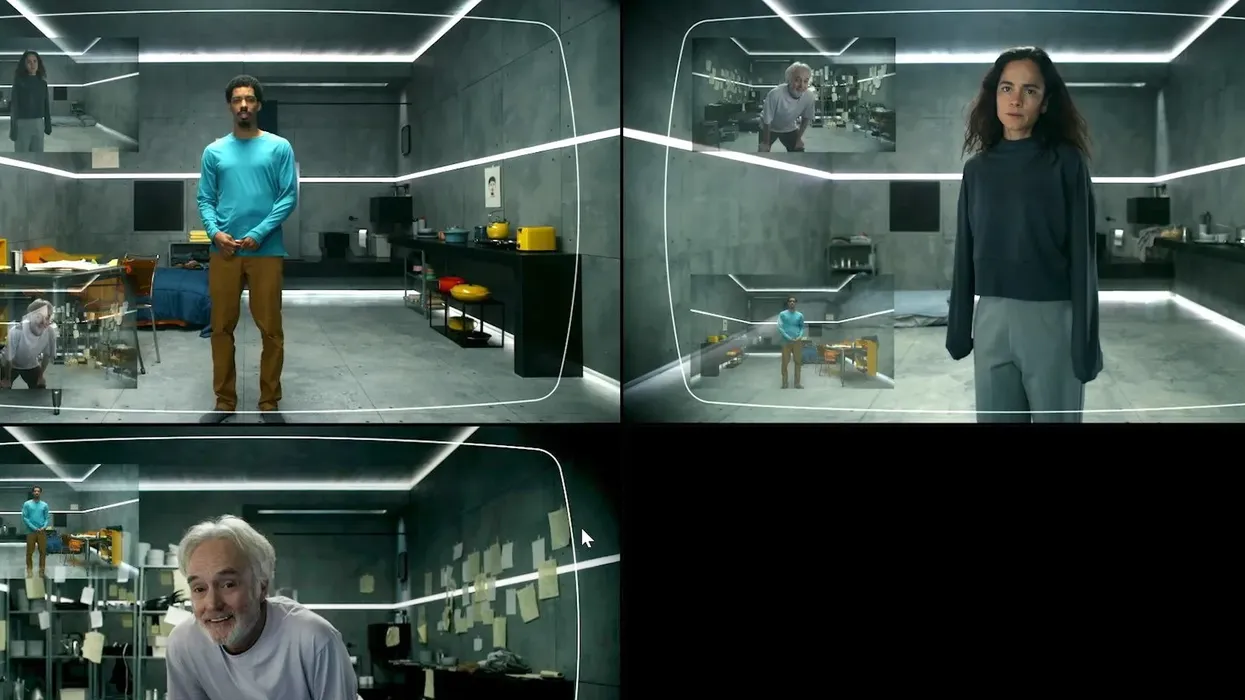

“SHARE?” is filmed entirely from only one fixed camera angle. I think when people hear that, they think that it must have been incredibly easy to make, but the exact opposite is true, with regard to both production and post-production. In the story, all characters are trapped alone in their own rooms and are able to communicate with each other only through a rudimentary computer in their wall. While shooting, it was very important to me that the actors could interact with each other in real-time, so we built three identical sets next to each other on a stage. Equally important was their ability to see each other, as well as the need to establish fixed eyelines to each of the elements on their screen, without which the reality of the movie would have been destroyed.

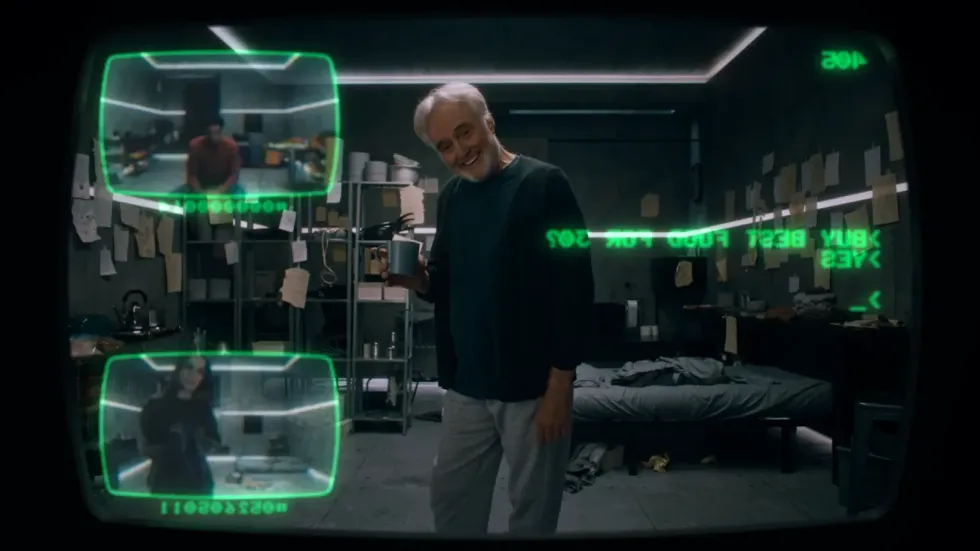

In order to achieve this, each set had a fixed camera integrated into a visual communication system that we created using Interrotrons (essentially, two-way teleprompters) connected to a live switching system. This allowed not only me, but each actor looking at their teleprompter to see a previsualization of the finished scene — that included not only the live feed of the cameras in the other rooms but also the computer interface as they typed and interacted with it. Motion Graphics Designer Phil Aupperle used After Effects to create the computer interface, which we used both as previs and for the finished scene. The first time I saw that this system actually worked on set was incredibly exciting and relieving, as up to that point, its functionality was completely theoretical.

What were some specific post-production challenges you faced that were unique to your project? How did you go about solving them?

Because of the unique way we filmed the movie, we had to innovate many processes in post. Most of the movie consists of shots that include a main image of a character and up to 3 smaller picture-in-picture (PIP) windows. I realized very quickly that editing a scene using just the main image would yield a very different cut than one that considered the main image along with the PIP windows.

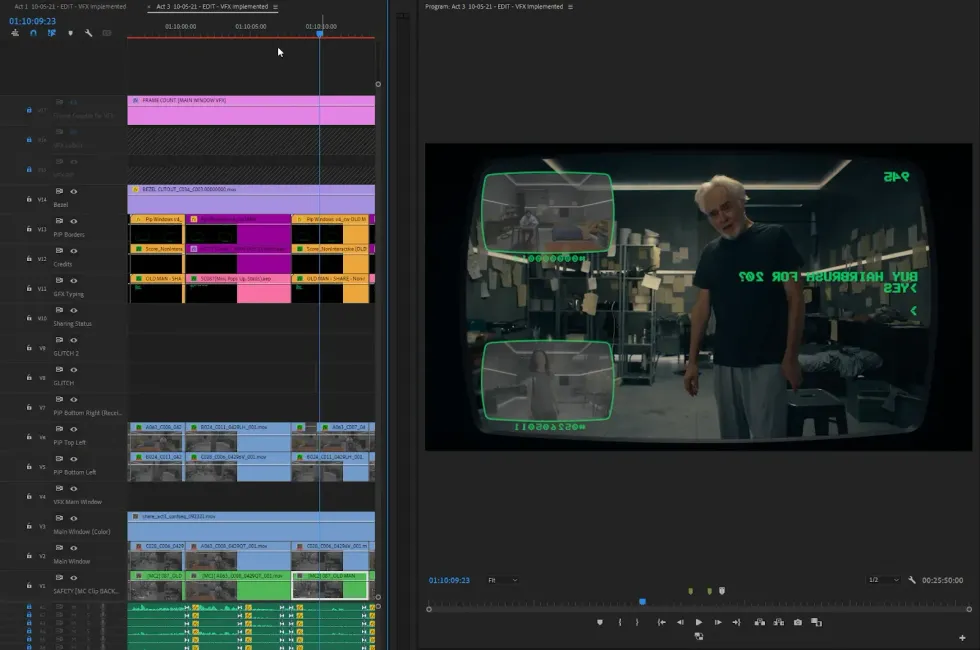

To solve this, assistant editor Christian Whittemore, created a multi-camera sequence for each shot that was composed of 3 nested layers. Each nest included the main image for a character, as well as the smaller PIP windows that character would see. This meant we often were playing 9 layers of HD ProRes LT video simultaneously. We never experienced any performance issues in Premiere with these multi-camera sequences as we were editing on fast SSD drives.

I then used these multi-camera sequences to make the initial rough edit of each scene, and then we used transcription to help us segment every take so I could choose the best main window performance for each cut. Sometimes the performances of the actors in the PIP windows in those takes happened to be best, but most of the time, I’d find better individual performances in other takes, so we then decomposed all of the multi-camera clips to their component shots and replaced those PIP takes with others.

Once a scene was locked, Whittemore exported it as a reference edit, brought it into a new After Effects file, and animated the computer interface using keyframes, including simulating realistic typing by the characters. We would sometimes have the character misspell, backspace, and then finish typing correctly to add realism. Elements such as each character’s “credits” counter were also animated this way.

What Adobe tools did you use on this project and why did you originally choose them? Were there any other third-party tools that helped enhance your workflow?

The complexity of the film made it crucial to execute as many effects as we could without leaving Premiere Pro. When we did, we used Dynamic Link from Premiere Pro to After Effects making it very simple. Even in early drafts, we were able to accomplish sophisticated looks for the computer interface entirely in Premiere, with simple tools like fast blur and blend modes. Later in the process, we utilized Red Giant Universe’s VHS and Analog plugins extensively to create the analog look of the picture in picture windows. These PIP windows “glitch” out throughout the film, so we built our own presets based on Red Giant’s glitch transitions to make these moments happen throughout the film quickly. Frischluft Lenscare was used to set and actively rack the focus of the graphics and monitor frame for every shot in the movie, depending upon the depth of each character in the room. The computer interface was created in After Effects, but Whittemore also created Motion Graphics templates (.mogrts) to edit some of the less complicated graphics directly in Premiere.

I could go on for quite a while about how invaluable Premiere and its integration with After Effects was to the project, and I’m not sure there are other solutions that would have made the process as seamless, especially for a small post-production team. Our sequences sometimes had up to 17 tracks of video, including the main image base layer, picture in picture windows, multiple layers of text interface, and the frame of the computer screen. We also on-lined and exported the movie from Premiere.

Do you use Frame.io as part of your workflow? If so, how do you use it and why did you choose it?

Dailies were uploaded to Frame.io each day during production. In post, it proved extremely helpful during the VFX review process, as I could circle problem areas of the frame for easy reference, and frame-accurate notes left no confusion about what part of a shot needed revisions.

If you could share one tip about Premiere Pro, what would it be?

Utilize as many keyboard shortcuts as possible. And if you have repeatable effects throughout a project, effect presets are a lifesaver.

Who is your creative inspiration and why?

My creative inspirations continue to change over time, but have included Lars Von Trier, Steven Soderbergh, Darren Aronofsky, David Fincher, Charlie Kaufman, Spike Jonze, Sasha Baron Cohen, and Chris Nolan. Really anyone playing with cinematic form or inventive modes of storytelling. Currently, that includes Nathan Fielder, Ari Aster, and Ruben Ostlund. I tend to put a premium on provocative, daring, and different.

What’s the toughest thing you’ve had to face in your career and how did you overcome it? What advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers or content creators?

Stay true to your vision and fight for it. I had a lot of people along the way try to dissuade me from making the film the way I did. One camera angle, with text backwards the entire movie, and only one person on screen for the 1st 15 minutes is not the easiest sell. But I eventually found producers and financiers that believed in the vision who allowed me to make “SHARE?” the way I intended.

This post was written by Kylee Pena and originally appeared on the Adobe Blog on December 4th, 2023.

Author: Sponsored Content

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.