There’s usually one film every year that breaks through the noise that no one saw coming. And this year, the film rose from the ocean and stomped on everything in its sight was Godzilla Minus One.

And it didn’t just change perspectives at the box office. Godzilla Minus One is the first Japanese movie to ever be nominated for a Best Visual Effects Academy Award. And it’s the first Godzilla movie to earn an Oscar nomination.

Today, I thought we could watch a video made by the film’s small effects team and then unpack just how they brought this movie to the big screen.

Sound good?

Let’s go!

The Visual Effects of ‘Godzilla Minus One’

When I watched this film, what shook me was just how much scope and scale was packed into every shot. You really felt the magnitude of Godzilla. And that helped increase the tension across the destruction.

In an interview with the Academy, writer-director Takashi Yamazaki said of the film, “I think Godzilla, as a franchise, is amazing, and the nomination speaks to a lot of what Godzilla Minus One is doing for Japanese films and Japanese cinema in general,” he continued, “This was a very small domestic production. We even did the VFX with a minimal team, and everyone did their best.”

So how does this minimal team pull off something incredible?

The Team Behind ‘Godzilla Minus One’

There were 35 people who worked on this movie, creating 610 shots in just eight months at Chōfu studio, and under the supervision of Yamazaki and direction of Kiyoko Shibuya.

That’s a staggering amount of work to do by that many people, and that fast.

But before that happened, there was a script. When asked about how he manufactured the VFX in his head while putting the story onto the page, Takashi Yamazaki said the following:

“Given our limited resources, we knew we had to maximize what we could do to put the best possible interpretation of Godzilla on this screen. From a VFX perspective, there was some degree of taking inventory of what the team was capable of. Having said that, I never let that distract me from writing a good story, which is the most fundamental component in making a good film. Once we have a good story, we think about what VFX we can do that would put the best spotlight on that story. In this instance, though, there were some exceptions to your point about the story informing the VFX or vice versa.

“We had a very young compositor—that was his role inside the company—but it turned out he loved VFX. He did some water simulations at home and brought them to the office one day. We said, ‘Oh wow, this is some pretty high-quality water simulation!’ That allowed me to write in more scenes that took place on the ocean. But it didn’t fundamentally change the story, just the ratio of different shots we took. It also helped that I was the writer, director, and VFX supervisor. That meant there were a lot of efficiencies happening within my head, like knowing the ultimate shot and how it would look on-screen, so at every stage of production, we knew that we were inching ourselves closer to that final product.”

The Intricate Design of Godzilla

After principal photography, the VFX work began. But a lot of decisions had already been made, like what they wanted this monster to look like.

Yamazaki told Maxon, “We wanted a vertical stance, with very thick and robust legs, giving the overall shape a mountain-like appearance. We focused on making the lower body very massive and the face frightening, yet unmistakably Godzilla.”

But it’s one thing to just say your goals, and another thing to do them.

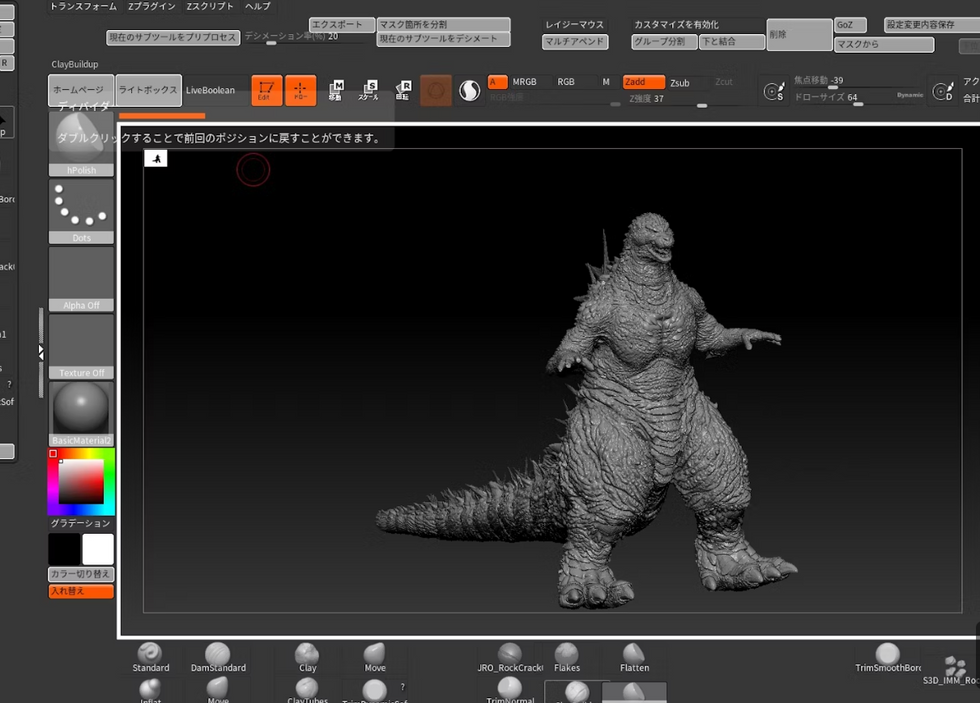

In that same Maxon interview, Yamazaki elaborated, “I made a rough 3D maquette in ZBrush and Mr. Taguchi took it from there as a 3D sculptor and modeler, adjusting the balance and adding incredible details. I trust his artistic sense greatly. We handled billions of polygons, so the model had to be converted into numerous displacement maps for rendering with Redshift. The workflow involved animating a relatively light model and applying various maps for the final render.”

For the final render, things got even crazier and more intricate.

Yamazaki explained, “If you zoom in even more, there’s a very complex pattern happening, and this level of detail, perhaps the resolution of both the color and the bumps, makes Godzilla feel all the more real. He used an incredible amount of polygons to achieve that look. For the head alone, it was 200 million polygons. The chest area is another 100 million. At one point, we were concerned about whether we would be able to render this thing onto the screen, because of the sheer amount of data that needed to be computed. Luckily, we employed various techniques to lighten some of the polygons and ensure Godzilla was renderable.”

What Other Programs Were Used to Finish ‘Godzilla Minus One’?

When it came to finishing the rest of the movie, Yamazaki and his team used the 3D animation software Houdini and Maya for design and Nuke for compositing.

As mentioned above, Yamazaki made a 3D design on ZBrush, anf Taguchi augmented the design by adding his own elements, including the insertion of polygons and rendering displacement maps using a program called Redshift.

The team retopologized the maquette design and displacement maps with Mudbox.

Takashi Yamazaki’s contributions to Godzilla Minus One as a writer, director, and VFX supervisor mark a significant milestone in the evolution of the Godzilla series.

By intertwining the latest advancements in visual effects with a deeply resonant historical narrative, Yamazaki has not only contributed a new chapter to the Godzilla legacy but has also redefined the parameters of monster cinema.

His ability to meld the tangible with the digital, the historical with the fantastical, underscores a masterful understanding of the genre and the technological tools at his disposal.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Author: Jason Hellerman

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.