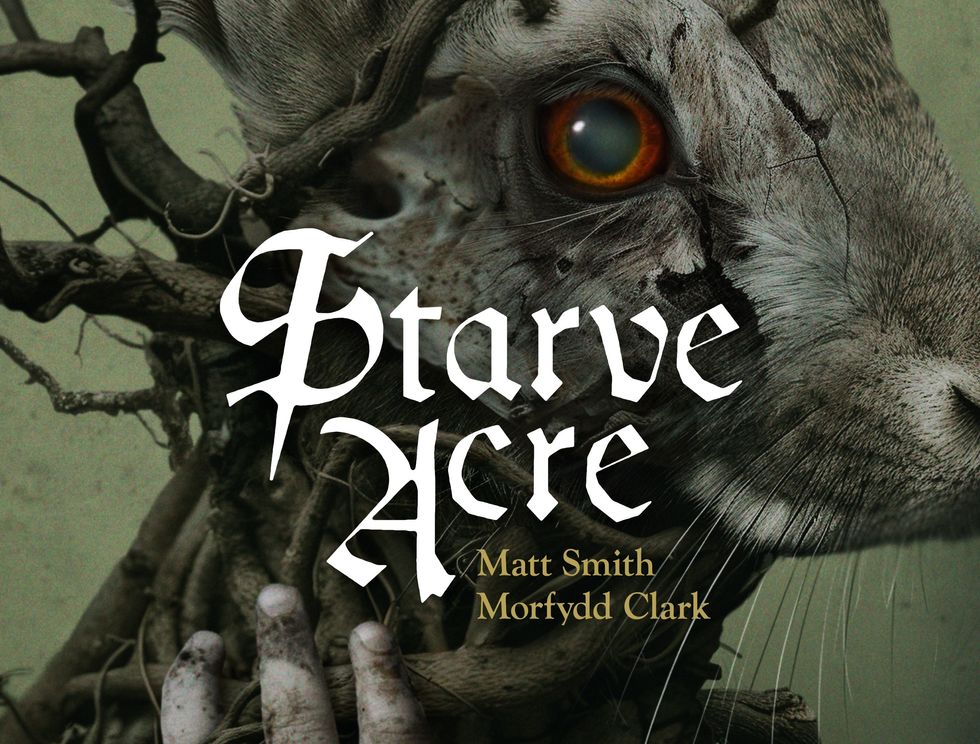

If there’s an environment that works best for folk horror, it’s probably the exquisite rolling moors of Yorkshire under gray clouds. For me, a movie lover who was raised on baby Gothic tales like The Secret Garden and later the grim romance of Jane Eyre, the new film Starve Acre is a splendidly dark and gloomy return to a beloved setting.

In Starve Acre, writer/director Daniel Kokotajlo brings to life the chilling tale of a family grappling with loss and mysteries surrounding their home. After a terrible death, husband Richard (Matt Smith) and wife Juliette (Morfydd Clark) search for meaning in faith and folktales.

Kokotajlo, a BAFTA-nominated filmmaker for his poignant religious drama Apostasy, premiered Starve Acre at BFI London Film Festival last year, and it will have its wide release this month.

As Kokotajlo continues to push the boundaries of contemporary horror, Starve Acre offers a glimpse into his evolving artistic journey and the lengths a director will go to make a low-budget production work. On a Zoom call with him recently, we delved into the inspiration behind the film, the challenges of its production, and the challenges of modern-day horror.

Starve Acre UK trailer starring Matt Smith & Morfydd Clark | In cinemas 6 Sep 2024 | BFI

www.youtube.com

Editor’s note: The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

No Film School: I know that you’ve spoken about being drawn to a sense of unease in the original novel. So how do you set about establishing that sense of unease as a visual storyteller?

Daniel Kokotajlo: I try to emulate the way that Andrew did it in the book, I think. He had a strong focus on a sense of place and a sense of time, the use of landscape and how that reflected certain characters’ emotions. It was just being aware of that, I think, and finding the right balance of tone as well.

We’re dealing with a very heavy subject, and so then it requires sensitivity. But then also there were things that came out of nowhere. There were shifts in tone that we had to be quite careful dealing with. But then, once all those things came together, it did then create that sense of uncannyness, a creeping feeling. It’s hard to explain. But definitely to do with a sense of place and the landscape and then how that manifests in terms of what the characters are doing, their emotions, and then also, of course, the sound design and then the music on top of that.

NFS: Are there specific moments where you see that shift in tone, and how did you approach them?

Kokotajlo: I just embraced it. It was in the book. It was unashamedly like old, old British storytelling, and I didn’t worry about it too much. I love that, in fact, the way it combines this deeply personal drama with these more ghost storytelling elements.

And I think you notice that in the film that it does start off in a certain way and takes a left turn at a certain point, and it suddenly becomes more of a ghost story. And then again, it shifts into another way, and we introduce other stylistic elements. And you might not be prepared for it or expect that to happen, but it all works.

I think it works because it all represents what [the characters are] experiencing, what grief does to people, and how they react. And suddenly your world opens up and it becomes this place that’s very hard to navigate, and things come out of nowhere, and strange things happen. And so then that made it okay to introduce certain elements for me.

Morfydd Clark in Starve Acre

Morfydd Clark in Starve Acre

Chris Harris/provided

NFS: I know that you shot in the thick of COVID protocols, which I’m sure was a challenge. But were there any other technical challenges on the film, and how did you overcome them?

Kokotajlo: Well, everything that could go wrong did go wrong, I think. And I’m probably not even allowed to talk about a lot of things that went wrong.

Some of the safer things to talk about are the weather, really. The weather killed us. Having a really complicated excavation down in a slope, in a field in the middle of the Yorkshire Dales, you can’t imagine how problematic that was. Because every morning, it was flooded, it would take an hour or two to sort out, and we had a very expensive prop buried in there, so that was getting damaged constantly.

We had seen set-up in the woods, a scene that I had to drop in the end. I could never get it shot. We had this very complicated scene at night in the woods, and then we got hit with a 50-mile-an-hour hailstorm, and branches came falling down and nearly hit people on the head. And so we had to abandon ship on that. And that’s something I couldn’t fix because that was the last night shoot. So I had to drop that.

And then another thing, I had four or five exteriors, scenes planned to shoot one day, but the evening before we found out we’d lost all of them. The council revoked our license to shoot, so then I was given one private street to shoot all my exteriors on. So then that was… [laughs]. I then spent all night trying to work out how to incorporate all these scenes into this one location.

So there was a lot of that going on. Every night I had lost a bunch of scenes, so then I had to incorporate them into the next day’s scenes. So I was rewriting the scripts most nights, but luckily everybody was on board with that. And I had actors who enjoyed that as well. I turn up with new scenes every day, and they’re excited by that, and we’d block it out and rehearse it and figure it out. And quite often, it made the scene richer because of that. There were more elements and more story beats and things sometimes.

Animals are very difficult to work with. And you always hear people say that. Because I was writing the script during COVID, I just didn’t care. I was like, “Man, I just want to get out and shoot a film and I’d love to work with animals and children and work in the landscape.”

But yeah, those proved to be incredibly difficult. The fox, particularly, you just cannot get a fox to do anything no matter what. Animal wranglers tell you they can train them to do certain things like stand still, but they can’t. I don’t know if you remember, but there’s only one shot of a fox in the film. I got more footage of that one fox trying to stand still and look towards camera than anything else in the film.

Gosh, what else? The puppeteering proved to be a challenge just schedule-wise, realistically. To get a convincing performance with a puppet, it takes time, and especially when you’re working on location as well in these small rooms, and you’ve got a crew of 15, 20 people, and then you’ve also got seven puppeteers operating this creature, it means that you’ve got one puppeteer hanging off the edge of a bath and someone else is hanging off the ceiling. So they don’t have much control over the puppet.

And so you do have to do quite a lot of takes to get it to look convincing. And quite often, that kind of stuff gets left to the end of the shoot as well because you want to shoot with the actors and get the good performances. Sometimes you end up with just five minutes to shoot something that you ideally need a whole day to do. So yeah, that was a challenge. But luckily the puppeteers, they were rehearsing on their own in a different room, so they got it down.

It was going so wrong in the end that I got a second camera out, and then I was setting up two scenes at the same time in different rooms. So I’d have one camera and one set up there with one actor and then another scene set up with another actor at the same time and just sort of go between and shoot two scenes at the same time.

NFS: I was going to ask about the puppet. So I assume the number of puppeteers is why you chose to shoot it tight.

Kokotajlo: It was a stylistic choice, as well, to try and gradually reveal it, in order to have at the beginning, just show certain things. A bit of its nose and paws and ears, and gradually reveal it. It didn’t quite work out that way because you had to show more of it. Certain parts I wanted it to be just on the kitchen table, that’s when you saw it for the first time, but we couldn’t really make that work. But yeah, it was a bit of both. It was a stylistic choice, but working in closeups did help with blocking and lighting as well.

NFS: What was your shoot schedule? How many days did you have?

Kokotajlo: Oh, good question. I can’t remember exactly. It was five weeks, but we got closed down because of a COVID outbreak, but then that worked out in our favor, so we got given two extra days. So it was like five weeks and two or three days, I think.

Starve Acre

Starve Acre

NFS: Do you have a favorite sequence on the film?

Kokotajlo: I really love the end scene. Mainly, again, because that was all shot with very little time. And without spoiling it, quite a lot of that scene was all shot in one take, but cut up into different shots. But because of the nature of how little time we had, I had to just keep the camera rolling and moved around and kept people moving. It’s quite complicated to block and we had certain props that we had to be careful with. So when I watch that back, it feels like it was very well planned out and I’m quite proud of the feel and the tempo of it.

NFS: What were you shooting on?

Kokotajlo: It was digital. We found some wicked old [Cooke] Xtal lenses, anamorphic ’70s lenses that had a bit of distortion and looked very appropriate for when the story is set. And then we printed it to a 35 mm negative. It was the cheapest service we could find. But that was also a decision we made because I knew it was going to create a dirtier image. And it came back and it was really dirty to the point where I had to do a bit of cleanup work on it because there was so much ink splashed all over the image. So I had to spend quite a bit of money fixing that.

But yeah, it gives it its own unique quality. I think it was the company we used. Yeah, there was no other company doing it like that. So it has its own kind of grain structure and does something interesting with the colors. I like the way it looks. I like how it beds in all the other elements, as well. The puppet work and the VFX, it suddenly makes it all feel cohesive and part of the same image.

NFS: What are the biggest challenges for you of working in the horror space?

Kokotajlo: It’s a good question because in Starve Acre, I guess I wasn’t really thinking about it. I was just excited that I found this story that was hard to pin down. It was a strange unidentifiable sort of genre in a way. And I was excited by that. And luckily I had the people there that wanted to make that kind of film as well.

But I feel the further you get in your career, the harder that gets. These opportunities don’t come along very often. And if I’m now wanting to work on a bigger budget, then I’ve got to talk in a more commercial way to backers and financiers. So then that brings its own challenges. How much can you stick to things you want to do, your own kind of style?

I love combining certain genre beats with drama and more honest storytelling. And I think horror, you can still do that. I just worry that especially right now that people are aware of quite a lot of horror films that are doing that and they want to push it into a more commercial space. It’s trying to strike that balance everybody’s doing all the time, between commerce and trying to do something interesting.

NFS: When you say more commercial horror, do you mean more traditional horror beats? I don’t know, the video nasties that you have over there, like that type of thing?

Kokotajlo: Yeah, I think so. And also just people wanting more logic and simple storylines. They want to know, understand what it is exactly straight away. So it’s a feeling I get this year more last year, in fact, just like if they can’t tell what it is or where it’s going to go or what problem this character has, immediately they just go off it.

NFS: I hope that’s not the case. I love a challenging film that doesn’t tell you everything.

Kokotajlo: Yeah, yeah, me too. I really hope this survives. These kind of creepier, unsettling films, sort of strange, weird films. It’s a certain tradition, like ghost storytelling and gothic storytelling, that deserves its own space and genre.

NFS: Do you have any advice for aspiring directors?

Kokotajlo: A big one for me was to tell a story that I knew. That was like with Apostasy, that was my personal experience. And at the time, there weren’t any other stories that I could find on screen that were about that subject. And I didn’t really want to do it. I didn’t think anybody would want to see it either. And I was kind of shocked and surprised at how many people took an interest in it, financiers and backers. So yeah, I think that’s a big one, man. Tell a story that you know, and sometimes you’ll be surprised at how that resonates with people.

NFS: Great advice. Is there anything else you wanted to add about Starve Acre?

Kokotajlo: Please go out and see it … Ignore what people say about it and try not to read too much on it, because it’s quite easy to spoil the film, I think. But yeah, go in expecting to be surprised in a certain way. It is a creepy, unsettling film, but it’s also, I think, entertaining and enjoyable. Yeah, please go see it.

Starve Acre is in theaters and on demand July 26, 2024.

Author: Jo Light

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.