Written by Masha Egieva

In early 2024, I finished my second short film as writer-director, “Saint Vassily”. A historical drama which takes place in 1982 USSR, “Saint Vassily” revolves around a self-righteous theological academy student, Vassily, preparing for Russian Orthodox priesthood. When his roommate goes missing, Vassily is tested by a KGB agent, who threatens to rescind his ordination unless he denounces his roommate.

To bring Saint Vassily to life, I worked with incredible filmmakers, including DP Arnaud Potier (Galveston, Aggro Dr1ft) and editor Helle le Fevre (The Souvenir, The Eternal Daughter). “Saint Vassily” premiered at HollyShorts Film Festival in LA this August. In this piece, I want to talk about the thought process behind the making of this film, and how a filmmaker can sometimes obstruct their own artistic process.

As a Russian-born filmmaker, “Saint Vassily” came from a feeling that everything I was writing at the time when Russia invaded Ukraine was irrelevant, and that I should be doing more meaningful and important work. Watching the war unfold before my eyes, documented in real-time, I felt the urge to talk about how today’s tragic reality became possible without speaking directly about Putin’s Russia. As a result, I made Saint Vassily, a study of moral compromise and what it leads to. While it is a historical drama, it was made to be relevant today, more than two years into the war.

Masha Egieva on set of “Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

Masha Egieva on set of “Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

Initially, I was going to make a documentary about the collaboration between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Soviet secret service, the notorious KGB. During the research process, I discovered testimonies, memoirs, letters from the then-students of Russian Orthodox theological academies, scattered across the vast empire that was the USSR, describing coercion, intimidation, blackmail of the young clergy by the agents of the State. There is one thing that unites those who initially wanted to serve the Church but ultimately agreed to collaborate with the KGB: compromise. I quickly realized that compromise would be my subject.

The more research I did, the more I felt like there was a dramatic core to these testimonies: the protagonists, the antagonists, their strengths, weaknesses and motivations were right there in front of me, waiting to be structured into a coherent, fictionalized story. Setting the story in a religious institution is a dramatic blessing: within the context of the Church, virtue and vice, the right and wrong, bear gravity unknown to the lay world, raising the dramatic stakes. This is how a documentary transformed into a narrative script which, two years in the making, became Saint Vassily.

The biggest challenge that I faced throughout the making of “Saint Vassily” was to speak about the processes that led to the Russian invasion of Ukraine while not turning an artwork into an ideological mouthpiece for my anti-Putinist, anti-war stance. While I felt the urgency to make “Saint Vassily”, I needed to make sure that I was creating a nuanced, authentic portrait of my protagonist, caught between giving up the dream of becoming a priest and denouncing his roommate.

When I was a student in Art History, theorizing about other people’s work and not creating anything of my own, I was adamant that the artist must be first and foremost concerned with the problems of art, and not political signaling. It is only by being preoccupied with their medium that they can make important, impactful work. Now that I am a filmmaker, I find it easier said than done.

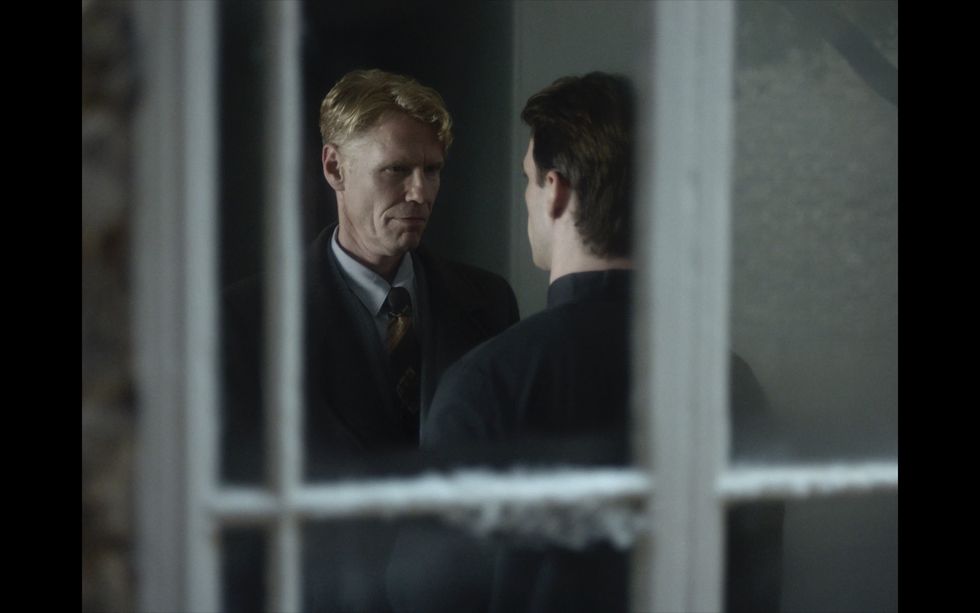

“Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

“Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

As I watched the war unfold, I kept asking myself what was at the core of Russia’s descent into a war-mongering totalitarian country. How did we allow for the State to become so all-powerful, and why have we failed to contain it? My feelings about the civil society in which I was brought up changed every day. I felt rage at the failure of my compatriots to stop Putin’s regime. I felt shame from my own powerlessness and inaction. I felt hatred for those who sold themselves to the regime. I felt empathy towards those who put themselves in direct danger as they opposed the State. I felt pity for those who lived in silence and fear. Those feelings had directly impacted how I treated my protagonist, who (spoiler alert) denounces his roommate and leaves his fate in the KGB’s hands, only to protect his own career within the Church.

In one of the first drafts of the script, I blamed my protagonist for his weakness in the face of the authoritarian State, making a grand statement that one must resist collaboration at all costs. In this draft, Vassily was villainesque, blinded by ambition from page one of the script. In a later draft, I justified my protagonist’s compromise, sending a message to the audience that most of us would crack under the pressure of the omnipotent State, and that it is unfair to expect heroism from ordinary citizens. In this draft, Vassily was an innocent country boy, oblivious to the dirty tricks one must pull to progress in the clerical ranks.

Finally, I let go of either. This is when I concentrated on studying my character, rather than making him fit my political sentiment in a given moment. In the end, I tried to neither judge nor justify my character’s choice, but, instead, deconstruct how and why he compromised.

“Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

“Saint Vassily” Courtesy of Polymath PR

I believe that the political power of art is that it provokes various thoughts, and not propagates a fully formed, pre-conceived thought to the viewer. In that way, the most impactful political art is that which is not preoccupied with politics, but with the problems of art itself. In the case of film, the best way to do justice to politically charged stories—as to any other kinds of stories—is to tell them well; to faithfully observe and study our characters and let them speak for themselves.

I can only hope that “Saint Vassily” will ignite conversation about the nature of moral compromise, and what one can do under the pressure of the State. This is what I wanted “Saint Vassily” to do: not send a message, but shine a light, provoke thought, and start a conversation.

Author: Guest Author

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.