Once you see a Brian De Palma movie, you’re never going to think about original filmmaking the same way again. He is the master of the macabre. His movies delight in violence, sex, and at times, bad taste. He’s not afraid to tackle subjects head-on, and he’s fearless when it comes to pastiche as inspiration. When people talk about the greatest directors of all time, he’s often a name left off the list.

Late film critic Pauline Kael never forgot De Palma, though, lauding his works and challenging viewers to see his uniqueness and fervor. When writing about the ending to his 1978 movie, The Fury, she said, “Imagine, Welles, Peckinpah, Scorsese, and Spielberg still stunned, bowing to the ground, choking with laughter.”

But at the heart of De Palma’s career is an overt love of movies and moviemaking. Its shown through his homages and story beat stealing and accentuated through his use of originality and intrigue to put his personal spin on tropes, via pastiche.

So why aren’t we talking more about De Palma?

Brian De Palma’s Style

Before we jump in, let’s get a definition out of the way. In the context of film and television, “pastiche” is a cinematic device that directly mimics the cinematography or scene work of another filmmaker through the direct imitation of iconic moments in that movie or TV show. And De Palma is a master of it.

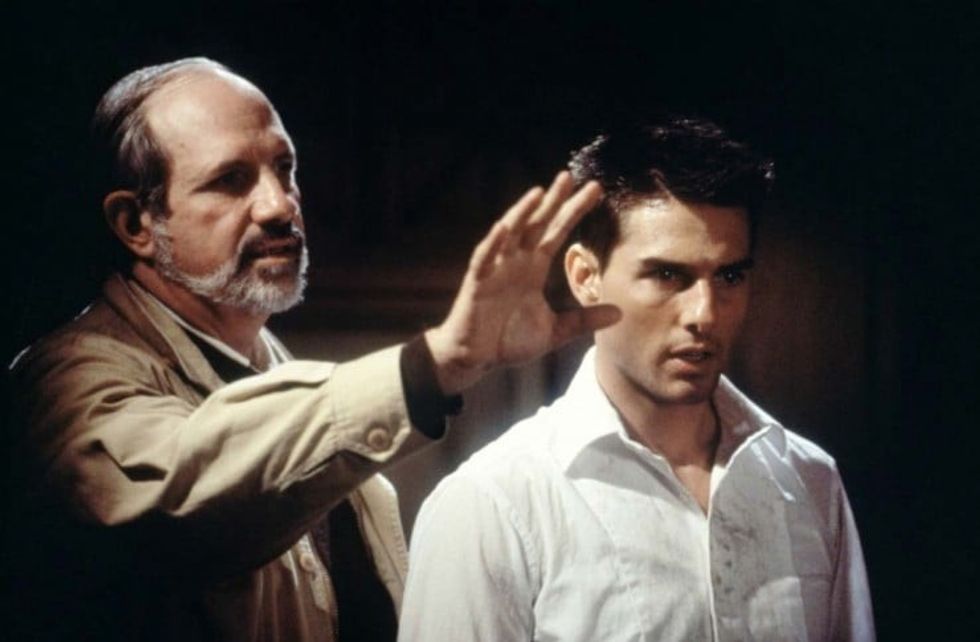

De Palma and Tom Cruise on ‘Mission: Impossible’

De Palma and Tom Cruise on ‘Mission: Impossible’

Credit: Paramount Pictures

Some De Palma Background

When it comes to original filmmakers, we’re in a bit of a drought today. Hollywood has prioritized tentpoles and IP filmmakers, and we’ve seen a downturn in people who build their own stories and make them. But in the late ’60s and early ’70s, when De Palma burst onto the scene, writer-directors were in a heydey.

He came up with a friend circle of Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas. De Palma stood out as the weird one in that group. His career was built on narrative intertextuality, with homages to directors like Alfred Hitchcock.

After making successful indie movies like Sisters and Obsession, he finally got the shot to direct the studio film, Carrie. It was a Stephen King adaptation of a very popular novel. And De Palma went in and made it his own. He flipped teen comedy tropes and planted them into horror movies, adding a twist ending and amping up the blood and violence. That hugely successful movie earned some of the cast Academy Award nominations.

From that point on, De Palma’s career followed a “one for them, one for me” trajectory. He’d do Dressed to Kill, then make sure he followed it up with a way more commercial Scarface. He’d direct Body Double but make sure he had The Untouchables, so he could eventually do Casualties of War. But even as his career waned and his projects ceased in the late ’90s and early 2000s, he still managed to sneak in elements of himself into the movies Hollywood let him make.

Like the absolutely incredible oner that opens Bonfire of the Vanities, the movie is most often cited as derailing his personal projects for a very long time.

De Palma and Pastiche

When some people brush De Palma aside, they usually cite his reliance on other movies to make some of his magnum opuses. Yes, it’s easy to see De Palma riffing on Hitchcock. Dressed to Kill takes sequences from Psycho and liberally borrows plot beats. Body Double takes the plot from Rear Window and adds in some Vertigo as well.

He borrows the title of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup and the plot of Coppola’s The Conversation for Blow Out. And The Untouchables‘ finale is a clear homage to the Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin.

Because he does this, many people have labeled him as “unoriginal.” That’s not remotely the case. De Palma can see the story so well that I think, like a great jazz artist, he likes to riff. While we laud people like Quentin Tarantino for doing this, I think we need to remember that De Palma was a pioneer. He studied classical Hollywood and found the parts he thought he could update.

This kind of storytelling was also a smart way to bring producers and actors into the fold. He could pitch his movies easily. “It’s Psycho with a bored housewife. It’s Rear Window with a struggling actor and a porn star.”

He also had a definitive style of shooting, one that hearkened back to the classics but that didn’t sell out the story to honor them. He had no problem changing the beats he borrowed into something servicing a story he knew felt modern. His killer reveal in Dressed to Kill not only is a huge twist, but it winks at you in a Normal Bates way, letting you know he knows what you thought was coming, and somehow he surprised you.

His absolute reconstruction of the Hollywood studio system in Body Double is not only a biting satire of the industry and how you have to sell your soul and body to be a part of it, but it’s an embracing of the sleaze and smut that gets people ahead.

De Palma is not someone just stealing beats, he’s an important artist with a point of view about life, love, war, and capitalism. Even his studio movies have those moments, although he has to let them simmer underneath the service. Instead, he winds up using cinematography to talk to us, with dutch angles, split diopter shots, and long, tracking pans that stew audiences in suspense.

Summing Up Brian De Palma’s Pastiche

I think De Palma is one of our unsung heroes of cinema. There are so few allowed to try his pathway today. And that’s kind of sad. He is a rebel of cinema who changed Hollywood for the better. There’s an excellent documentary made on De Palma and his choices that I encourage you to check out if you want to dig deeper into his filmography. While his movies are not for everyone, they’re a constant reminder that it’s okay to steal and homage, as long as you have something to say about the world.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Author: Jason Hellerman

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.