Sound design is an art of film craft we don’t give enough credit. Building a soundscape for any movie is a tough, nuanced role that can make or break the atmosphere and story for the audience if not handled with delicate care. So what if your building a soundscape for an otherworldly afterlife with a suave ghoul with an affection for burps and gurgles, not to mention a monster Beetlejuice baby running around?

This is a task that veteran sound designer Jimmy Boyle took the reigns on for Tim Burton’s fun-as-heck followup to his ’90s classic in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice.

Not only did Jimmy live up to the hype of the legacy sandbox of burps and gurgles from the original Beetlejuice, he also modernized and added to the world in interesting and immersive ways. Based on his credits (including everything from James Bond to The Northman), Jimmy hands down knows how to build an auditory world. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice only cements his talents as a world class maestro in post sound.

Below, we chat with Jimmy about all things sound design—from his process and technique to how he builds his folly SFX library. Read it with your eyes for the sake of your ears!

Editor’s note: the following interview is edited for length and clarity.

Getting Started as a Sound Designer

“I remember when I turned up at this company and there were samples sitting everywhere, and pull gear. I was watching things like Jurassic Park and Terminator 2, and it seems like they were just plugging in SFX to make all this cool. [I tried that] and I probably just made a load of junk. I didn’t realize that some of those things are about finding the right sounds and about actually knowing what it is you are trying to do and what story you’re trying to tell, quite honestly.

That took a little time to figure out. You have to learn the trade and the basics. I was transferring rushes, doing rushes in the morning and then conforming dialogue sessions and doing all the assistant jobs, loading in music cues, or whatever anyone needed me to do.

In the meantime, I was picking up [sound design techniques]. I worked in a Foley stage and Foley editing, and then I got an idea—it takes the time. It’s not just about the technology, it’s about actually having an idea of what you want to do and the story that you’re trying to tell. When I first started, most of the big films really were still being cut on 35mm sound and picture—picture carried on for quite a while after sound went mainly over to digital. But when I first started we used an eight track green screen audio file, an MS machine was 110,000 pounds. It laid up eight tracks of audio. You’d have do a one reel of dialogue that was very simple in those days. Not multi-tracks, two tracks, you can lay up one reel of dialogue, cut one reel of dialogue, and then you had to back everything up and clear the machine because there wasn’t enough storage. It was a while ago.

The weird thing is that I think all those cool films that were being made then, the sound designers, they’ve been doing it very, very long time obviously, making very cool sounding movies with not a lot. For me, the thing that I’ve carried on with is that just because we can have hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of tracks now, there’s not always a reason to—it’s the simplicity.

You pick the right sounds rather than laying up 20 and hoping that they kind of merge together. That’s where you get the term “brown.”

Honing Your Craft as a Sound Designer

“Just exactly that really I just always try to try to, obviously there’s certain films that become spectacles in their own rights within the scenes, but for me it’s always about stalking and I try to just start tell that as simply as possible and first of all, just look at what sound needs to do to help tell the story. And sometimes of course like say you jump, you’ve got a scene where spacecraft are flying down, aliens are turning up, they have to have their own, they have to have their own signatures and characters. But again, that really is story. I mean, you’ve got to figure out how you describe these things and how you pick the tone of what they are to help tell the story really.

And for me, that’s where I like to start. Yes, you know what you’ve got to do to make something sound better—you’ve got to get the dialogue. It’s got to be nice, you’ve got to get it sound as good as it possibly can. That for me is probably the most important, depending on the type of film, but nine times out 10, get the dialogue as good as it can be so that everyone can hear it and everyone can understand it. Then I just look at the film and watch it. I sit there and go, “What would I want to hear would I want to be told at this point?”

Here it’s not about sound effects, it’s about music and dialogue, and here it’s just about music, and then here it’s some crazy action thing and it’s all about effects and dialogue, whatever it be. For me, it’s not being afraid to try and make those choices and just be brave, really. Because it is difficult sometimes. Sometimes you don’t know. Sometimes you sit there and go, I just can’t figure out how to play the scene. And that’s part of the job, is to figure out how you do that.

That’s the other thing for sound designers, it’s just making sure you’re not creating something that you think is great. And then the music comes in, it’s all out here with all music and it doesn’t compliment the film, or the music steps all over the dialogue of the storytelling. It’s quite tricky sometimes to make all those things work.”

Jimmy’s Approach to ‘Beetlejuice Beetlejuice’

“I was a big fan of the original film [Beetlejuice]. I’d seen it a lot of times, but I watched it again and again and again and would refresh my memory. I think a big part of it for me was just trying to make sure that I paid attention to that first film and certain things that they’d done in that film that you really can bring up to date more, I guess. Things like the Sand Worm. There’s all sorts of things in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice that are brand new, obviously, but then there’s things that also are nice to update little bit.

Something I noticed in the first film was that every time they’re sitting having dinner and it’s quiet, there’s this awkward color of silences, you can hear the crickets, or whatever, it’s the insects outside, but they’re played in a way that they’re almost overplayed, but it works.

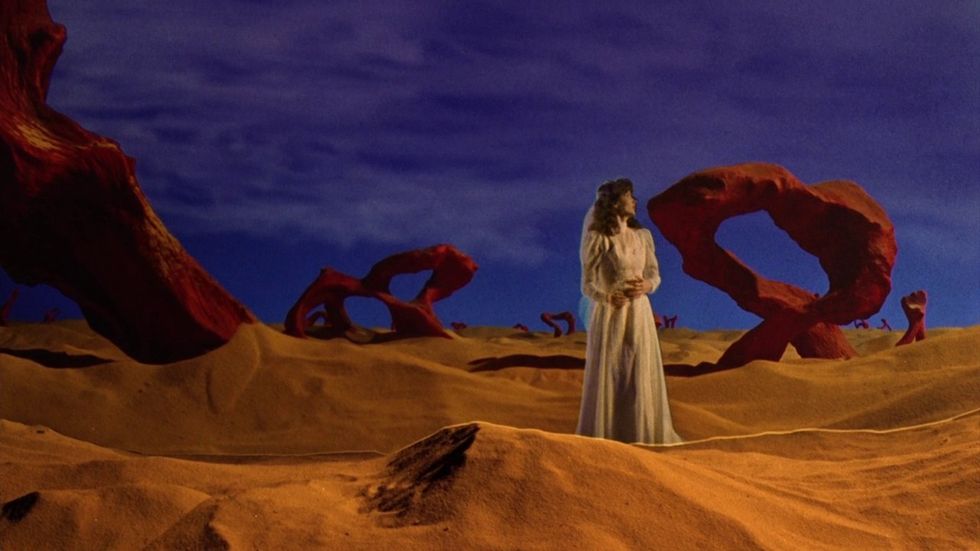

For me, little moments like that where you kind of go, there’s a reason that was done. If there’s those same opportunities and it helps the story, then that’s what I’ll try to do. We’ll try to do. So I think first of all it was watching the original film just for reference, which was great. And then really it was meeting with Tim [Burton]. The first time I met with Tim was just to come on and make a start for some very early stuff that he wanted to focus on that was most important for him. And then that was really figuring out things like what’s the atmosphere of—I always mess this up—I should just say Afterlife. Some of us would call it the Underworld

Especially when we first get introduced to that world, that was a big thing for Tim. What is it? It’s got to be strange. It’s got to be very different. We’ve just come from New York, it’s got to be very different. I think the film very cleverly plays on old Americana kind of physical things that were in places. So the waiting room, with the chime and getting a ticket, and all those things. That’s quite cool. So when they first get down there, we’ve got these flashing lights and it was like they will make ’em, although they’re kind of just old style lights that where the breakers come on and off or whatever, but at the same time we make them slightly strange and make them something else.

It was just having fun with those kind of things, which I think the first film did very well as well. You come in the place and there’s a guy being eaten by a shark ,and the lady that’s in half ,and all that kind of of stuff—an escape artist who’s stuck in this box, a lady whose been eaten by cats.

Lots of that became the atmosphere as well. Really by the time you put the details in for those, and especially once you’ve described the Afterlife you kind can settle into more of a course.”

Building a Folly Library as a Sound Designer

“All and above? Really everything. I mean as far as folly went we go and shoot everything for folly wise, set effects wise, yeah, we did lots of recording. One on the very top of Tim’s list to start with was the [Beetlejuice] baby, and I did a version where I recorded myself trying to do it because I want this thing to be horrific, monstrous. He’s said no, it’s not a monstrous, it’s like a baby. Then I was like, okay, but this seems to be a normal baby, but sort of scary. And then I saw some baby sounds that I had and can’t remember why. Then I just messed with them, really.

For the Shrink scene where they fall down into couples therapy, that was a bit of me, a bit of a baby that I messed around with on a turntable to move the pitch to make it almost cartoon and comedy, and then a bit of Jack Russell in there where it’s gnawing on her leg.

I have a very, very big library of stuff I’ve collected as well. I’ve recorded libraries of things. But normally will just go out and record bits and pieces, whatever it happens to be that we need as well.”

Advice for Aspiring Sound Designers

“That’s a really tricky one, because obviously there’s a lot of courses out there that you can do that I think are very important. There weren’t a lot when I was getting into this—[sound design] wasn’t something that was specialized as far as education goes. There’s good places to go to learn the techniques and the basics and the technology.

But I’ve always wondered how that works because to me, surely it’s like try and teach someone to be a great painter. You can teach people the basics, but I don’t really know how you get past that, how you teach someone to think differently, to come up with their own style and their own flare and their own way of doing things.

So I would say, yeah, go out there and get in however you can. Get a basic understanding of the technology and how we do things and how it all works. And then, yeah, if there’s something that you’re passionate about, just get in wherever you can.”

Author: Grant Vance

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.