In a film where every bump, word, and moment of silence carries weight, sound becomes more than just background noise. It’s part of the tension built into every scene, like the creaking foundation of a very creepy, maze-like house.

Today, we’re looking at Beck and Woods’ Heretic, a psychological thriller starring Hugh Grant that follows two young religious women entangled in a dangerous game within a stranger’s house. Sound designer/sound supervisor Eugenio Battaglia and Emmy-nominated re-recording mixer Michael Babcock were tasked with building an auditory landscape that amplifies the story’s spiritual unease and more immediate earthly dangers.

Although Battaglia and Babcock were both busy in different booths on the day we spoke, they were kind of enough to jump on Zoom and talk us through their playbook for this unique story.

Heretic is a dialogue-heavy film that also utilizes big moments of silence—how should beginners try to find those moments themselves? What advice do they have for people new to sound?

Find this out and more below.

– YouTube

www.youtube.com

Editor’s note: The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

No Film School: How do you approach the use of sound to build suspense?

Babcock: The sound is one of the top things Scott and Bryan, the directors, were able to use to build that tension. Hugh’s performance and the story in general get darker as the movie progresses, the story progresses. And the sound’s doing that, the sound keeps getting darker and darker.

So pacing-wise, things got more aggressive, things got more immersive, and they got to some degree deeper. They certainly get louder and more dynamic, and there’s a lot of story that you don’t see. It’s not just three people talking in rooms. There’s a lot of darkness support, something I just kind of invented off the top of my head right now. It gets a lot denser as it goes on.

NFS: Can I ask what you mean by darker sound?

Babcock: Eugenio, sound design-wise, provided the darkness. There was a lot of handshaking between music and what sound design was. In fact, some things that read as that are actually just strictly what Eugenio did sound design-wise. … We were just talking about this yesterday about [how] you don’t necessarily know what the “horror” is that’s coming. Is it supernatural? What is the game that Hugh sucked them all into?

So sounds are getting deeper, sounds are getting more aggressive. And by sounds, I mean things that you’re not necessarily seeing, and then also the things that you’re seeing on set … you should talk about some of your darkness that I pushed as far as I could.

Battaglia: The intention of this film is to give tension through dialogue more than anything. It’s not like a classic horror film where it is full of jump scares or tropey things like that. Most of the tension comes from what the characters are saying to each other. I think sound works on a more subconscious level, a more subtle level. I think what Mike means with the darkness is, as the movie progresses, I think there are elements that I’m using that play a little bit of the trauma that one of the characters has.

If you have the charisma of Hugh Grant going on, sometimes it plays a little bit as a comedy in some parts, but then he’ll come and say something really serious, and then that’s where the sounds around you start to shift to a more ominous tone.

Or, for example, if you pay close attention, every single segment of the film has a ticking element to it. If you’re outside, you have rain. Once you’re inside, you have clocks, you have that water device, the Japanese water device, the shishi-odoshi. It’s a fine balance of when you hear these ticks and when not.

But when something starts to happen that is supposed to give tension in the story, you can hear these ticks getting gradually louder, sometimes even faster, deeper. You start to hear the groans of the wood floor, the storm outside putting pressure on them. It’s little shifts in the environment that start to give tension without you noticing. That’s a bit of the darkness.

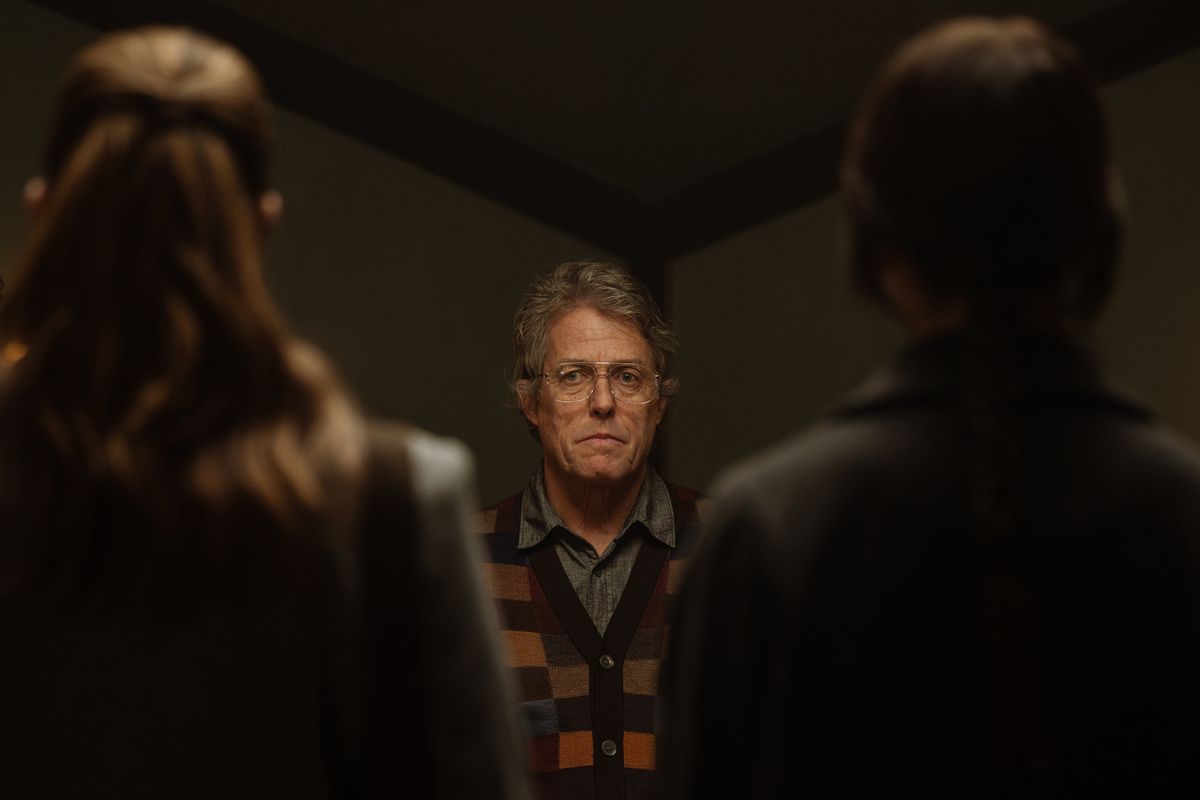

Hugh Grant in Heretic

Hugh Grant in Heretic

Kimberley French

NFS: There are moments of very dense silence too. How do you approach that?

Babcock: Deliberately. Those guys are always, always evaluating by scene, by word, by everything of how can they intensify a moment. So it’s picking those places wherever you need a contrast. So you’re very deliberately stopping a music cue. Not necessarily so it’s obvious, but you’re pulling things out. So the next thing has a moment to really read. And there’s a lot of places in here.

One of my favorite sonic places is where the prophet “dies.” You’re actually not sure what is happening. But to me that’s a good example of not doing the on-the-nose thing, sound-wise. Using deepness. It’s kind of like her heartbeat is stopping or slowing down, and then she hits the table, and you just don’t hear her head hit the table. It’s just loud. It’s very deliberate. So you have that super contrast.

The visual is great, but it really is a sound moment. If you’re just watching the scene, and somebody slams their head down on the table, it’s just, “Well, that was kind of weird.” But that moment is so heightened because you’re feeling emotion, you’re feeling the tension, you’re feeling the darkness. It’s more of a feeling than it is the on-the-nose, “Here’s what’s going on in the scene,” which is kind of indicative of the entire movie.

Battaglia: I think in every movie, silence can play to a different degree, where if you have something very loud going on, tons of sound effects, like music, horror, and then you go straight to silence, it’s always like a stylized moment. But here, I think it also plays to our advantage even more because you’re so used to hearing them talk throughout the whole film that when someone says something awkward or kind of weird, then the use of silence just gives you so much more tension.

It’s not like you go full to silence, but now that the characters have stopped talking, then you can start hearing the little details of the room around them, like the creaking, the clocks, the environment outside. And I think that just gives you a really uncomfortable feeling to just stop, abruptly, the dialogue. In real life, if you’re just talking and someone says something awkward, it’s that awkward silence that everybody feels. I think in the film, it’s so full of music and dialogue that when you choose those moments to place silence, it really, really feels heightened to me.

Babcock: And actually, you were asking about pacing. The picture editing really was a nice roadmap for that. It made it almost rhythmic in the places that we all chose to do that because they were playing up awkward silences. There are a couple extra frames when things are feeling uncomfortable, they’re holding on shots, they’re holding on performances for that reason, or they’re speeding things up. But it’s done very organically. The picture editing is great on this. Justin [Li] did great work.

Battaglia: Shout out to Justin.

Sophie Thatcher, Chloe East in Heretic

Sophie Thatcher, Chloe East in Heretic

Kimberley French

NFS: If there are those quieter moments, do you have any advice on how to start building those soundscapes?

Babcock: To me, that’s an important question, because any chance we can influence somebody who wants to use, either use that tool as a sound designer or use that tool as a filmmaker, director, whatever, it’s such an opportunity. I want to have a really good answer for this, just to encourage people to use sound as a tool.

I come from music, I have a jazz saxophone degree, and what you do in jazz is you borrow a lot of ideas and make them your own. So I think whatever story you’re trying to tell, I think watch something that’s similar and just see how they did it. “Oh, this is how this filmmaker did it.” Then you find a way to make your own, because obviously you have something that hits your heart. I think that would be my starting answer. It’s always good to reference other things that hit you.

Battaglia: I think as sound people, we value silence a lot, and it’s always one of the most impactful tools you can use. But you have to know exactly when to use it, because it’s not like you can have just a silent movie and have the impact of sound be noticeable. Even if you have a quiet film, and you think being subtle and being quiet works, you still need to have that dynamic.

I think maybe something that I would suggest is to try not to use sound like silence right away. I would suggest thinking of it as sculpting a sculpture. You start with a big mass of sound. Usually, when I’m designing, I don’t even think too much about, “Oh, this is the right sound, this not.” I just start throwing sounds, whatever it is. Whatever I find is like, “Okay, this is kind of it, but might not be it.” Just paste everything in there, and then from there, you start sculpting things up.

I think the magic of sound, and especially silence, is once you have something dense to work with and then you start subtracting stuff, to the point where you can get to full silence, I think that’s when you get the real weight of silence as a tool.

NFS: I love that analogy.

Babcock: I love that answer a lot. As someone who also does sound design, to me, that’s a good reminder. It’s kind of getting out of your own way and throwing things at it and then having emotional reactions to it.

Scott Beck, Chloe East, Bryan Woods behind the scenes of Heretic

Scott Beck, Chloe East, Bryan Woods behind the scenes of Heretic

Kimberley French

NFS: Are there any other things that you did to reflect the characters here?

Battaglia: I was talking to Michael about this too, and I think we both managed to collaborate on this. I think the original concept we had was to play the sonic design of this to be as if you were in a board game with them.

We played with the analogy of Monopoly and all of that, but if you think about it, you are traveling with these characters through this house in phases. And to me, that felt kind of like a game. There are levels. As you start with them—and this kind of ties with what Mike was saying about the sound getting deeper and darker—the sounds that we’re using are very reminiscent of a board game. It’s like wooden stuff, wooden creeks that shift. As the story progresses, you hear things shifting, things rolling, creaking, moving.

That also helps with the pace, too. “Okay, we just had this 15-minute piece of dialogue, and then there’s this catalyst that happened.” Then you have a shift in sound, sort of like, “Okay, this is the next phase of the game.” It’s a big moment. It’s a big sound that shifts and pushes you to the next thing. Now it’s a hallway, now it’s a different room. Now you’re underground. It’s not necessarily tied to a character, but it’s tied to the three of them at the same time. But to me, it feels like, as an audience, you start moving along in the game with them.

Babcock: There’s a vocabulary. Even some of the even more wild sound design things that you did, it does feel like it’s organically manipulated things. Creaking is definitely something.

As a sound designer, it’s good for each movie to have a vocabulary. You go and record sounds. You have sounds that you manipulate. But it’s good to have a starting point where you could take a wood creak, and you can make that sound like a lot of different things. It’s a jumping-off point of giving a movie, giving a story, a very specific feel.

Even if you’re using that starting point for all kinds of different, whether it’s whooshes or tension, you can take a deep creak, and then you manipulate it in a way that it sounds like it’s not even a deep creak, but it’s something where it all feels like it’s this particular thing going on.

Battaglia: Like a sound palette.

Babcock: Yeah. Actually, I just realized now a lot of your sounds … there are a few tension things that whip around the room that you start getting a taste of the very first time that Barnes—there’s a heightened moment where she realizes that what she’s smelling is not blueberry pie, it’s actually this candle. That is definitely a turn in the movie where it starts going dark.

Battaglia: In my mind, as she’s spinning the candle, it’s like she’s spinning a wheel, kind of like a Russian roulette. “Okay, the game has officially started, you’re trapped. What are you going to do?”

That creaking sound happens throughout the whole film. Later on in the underground cavern, you hear that spinning like crazy. To me, that’s kind of the concept, trying to make it sound old-timey, analog, like an old, twisted, wooden creepy game.

Hugh Grant in HereticKimberley French

Hugh Grant in HereticKimberley French

NFS: You’ve given a lot of good advice, but do you have anything else that you would say a beginner working in sound needs to know immediately?

Battaglia: It’s such an important question. I don’t want to repeat myself, but I recently had a person that wanted to get into sound sit behind me and just see what I do. Because I wanted to show her what I do without having to give her a class. So she sat behind me, and I started going at it. I had to design a logo for a film company.

Just don’t think about it too much, just think more about the feel, not the sound, and just start throwing things. And then think more about the sync, the tempo of things. Once you have something like a maquette built with any sounds, then you start replacing sounds. Then you start taking sounds out, manipulating them.

At the end of the day, you will get somewhere if you just put the time in and get inspired. But at the beginning, it’s always a mess. Just start throwing things, start matching the tempo that you want to match. If it’s not the right sound, don’t worry about it. It’ll get replaced, it’ll get manipulated at some point. Just prioritize tempo and feel.

Babcock: Like a lot of things in film and in general, it’s very much a mentoring kind of field, an experience field. What I would say to somebody who really wants to get into it is, keep listening to movies, keep listening to music. Especially cinematic-type music, and not necessarily orchestral—certainly that—but densely produced music. Cinematic is a very broad word, but I would listen to progressive rock.

Battaglia: Oh, progressive rock.

Babcock: Yeah, a 20-minute rock oeuvre of something. I find that’s very informative to figuring out what it is that you’re gravitating toward. That probably fuels you. And then you start making connections to, “Oh, they may have used that.” Things actually come together very fast once you see actually how it’s done.

So if you really want to do sound, just keep watching and listening to things and paying attention to like, “Oh, this is music. Oh, this isn’t music.” Just know that in most good art, a lot of very deliberate decisions that hopefully you don’t notice have been made. So yeah, keep listening.

Battaglia: I would even say, to elaborate on that, just borrow from other mediums. If you want to do horror films, don’t just watch horror films. I love progressive rock music, and I’ve definitely found sounds there that are like, “How the heck did they do that?” And I’m trying to copy that sound that they did there, the way they jump from a crazy sound to a little sound.

So watch cartoons, watch drama, watch all stuff. Definitely try to broaden, even if you’re a horror fan and you just want to do horror, if you just try to listen to horror, you’re not really going to get out of the box for your sound.

Babcock: Yeah, that’s a good point. Every genre of movie can inform the other genre. Same thing with music.

Author: Jo Light

This article comes from No Film School and can be read on the original site.